The ever-erudite Rob Reid dropped me an email a little while ago asking some questions for a paper he's writing on games and performance. Rob is one of the architects of Pop-Up Playground, the Melbourne gathering that has brought together a whole fascinating world of participatory makers, from digital gaming to interactive theatre to roleplaying to escape rooms, and on.

It felt like a good opportunity to wrap some thinking around Boho's practice, where it's come from, how we think about our work, what we're aiming for next. So, here goes.

How do you approach the design process for your interactive work?

Boho’s process really centres around working with research scientists - typically climate or systems scientists, but also urban designers, epidemiologists… Our shows usually draw on concepts from sustainability science, systems thinking, game theory, network theory, complex systems science, resilience - these fields which are often gathered together under a broad heading of ‘complexity’.

Basically, we’re looking at any sort of system in which lots of different elements are interconnected, and what arises from those interconnections. That’s the raw material for our games.

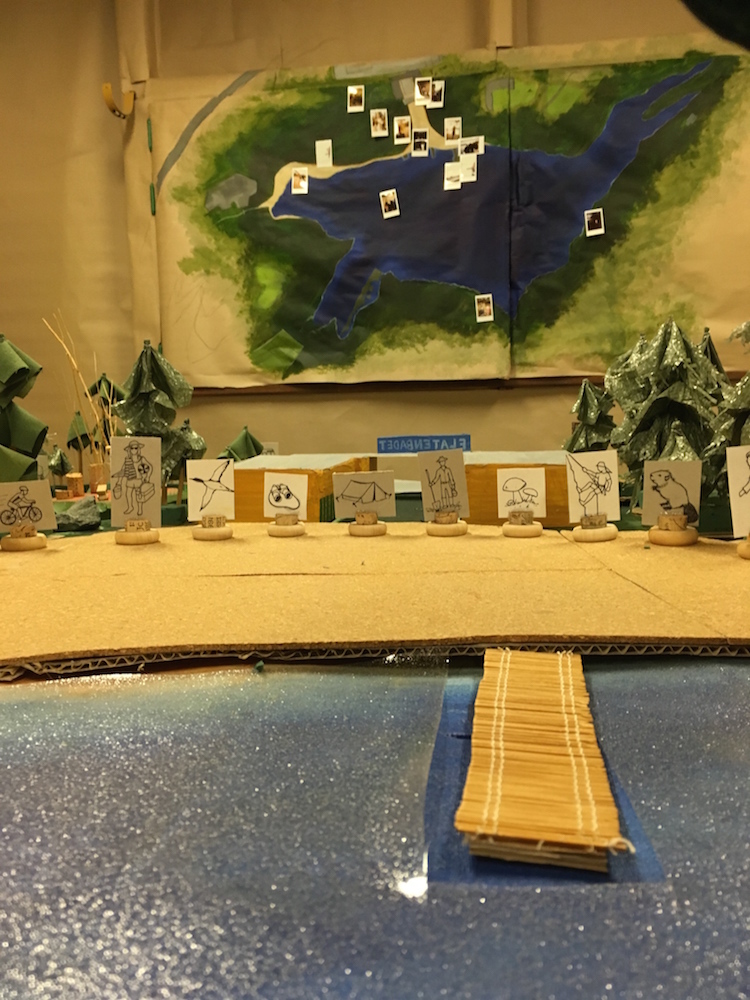

Working with scientists, we’ll go back and forth with them, building up our understanding of the system - whatever that system is - and creating a systems model. That model - which usually looks like a flowchart diagram, plus a whole series of maps, lists, other visualisations - becomes the basis for the show we build.

An example of the kinds of systems models we construct / adapt in our work.

An example of the kinds of systems models we construct / adapt in our work.

We then go through that systems model, looking for key linkages and systems dynamics we can turn into games.

In the last couple of years, we’ve started breaking things down into two kinds of interactive activities - what we’ve dubbed ‘skilltesters’ and ‘games’.

‘Games’, in this parlance, involve choice - any kind of decision-making, resource allocation, negotiation, etc. Anything where the audience needs to predict how the system will behave, and make a call about what they’d like to see happen. Things where they have to use their strategic brain.

The other kind are ‘skilltesters’ - games where the purpose is just to win. Can you fly this bird over here holding it between two sticks, can you sort these counters out into piles of different colours in less than 30 seconds, etc… These games are often more active, more playful, and we use them to give us inputs into our system model, so we can read out different scenarios. But we don’t hinge big choices on them.

Most shows will have a mix of these kinds of activities - some games where the audience is making key decisions, thinking through problems and coming up with strategic solutions, and some skilltesters where we’re introducing ideas more playfully, giving them a quick input into the show without too much weight being placed upon their choices.

How do you account for the unexpected in your work?

Look, we’re not improvisers - we build a structure with some different pathways, some resilience to shock etc, and then we guide audiences through it. There’s room for discussion, but in some senses there’s still the chance that the audience can break the show.

That said, one major advantage we have in building an experience is that we’re very transparent with our aims - ‘we’re here to talk about this concept, we’ve made these games that do that, here’s how it’s gonna work’. The performers are usually playing themselves, facilitating and helping the audience. So, for example, when Nathan was running a piece of ours called Volleyball Farm for a Forum for the Future event in London in Nov, the game broke because we’d never calibrated it for more than 5 players. But Nathan was able to discuss the intention behind playing the game, what point we wanted to illustrate, and that worked almost as well.

Can you describe the encounter between a participating audience and your work? (ie, what's it like to play?)

We go for gentle, non-confrontational, casual. Me, I get more anxious and stressed as a participant in interactive shows than anyone, and we make putting the audience at ease the key watchword.

So you’ll be met - in say a foyer, if we’re doing it in a theatre - and you’ll be told what’s going to happen, and you’ll be guided to a table, or to your seat - given a little more of a heads up about what’s going to happen - and then you’ll be introduced to the facilitators, and then you get your hands on whatever it is. Gentle, all the time.

The games themselves, often are drawn from boardgaming, and there’s a well established practice in boardgaming of how to introduce rulesets to players - good, thoughtful advice I think we’d do well to learn from. There’s an order to how you introduce information:

1. Who you are in the game2. What your objective is3. How you achieve that objective4. What does a turn consist of

and so on. Not always appropriate, but it’s nice to have a clear, logical structure for how information goes.

The experience is often divided roughly into three different forms: games/interactive components, theatre/narrative, and performance lecture. We’d tend to cycle between these three forms rapidly over the course of a show, with the weight shifting between them as we build to the end.

How does narrative/mood/meaning emerge from the experience of your work?

It all happens in the post-show discussions!

Well, mostly. We usually build a show with a post-show chat built in - a conversation with a guest scientist or an expert in the field we’re discussing. Then we’ll have a glass of wine, and a really informal conversation with the audience. That’s where the ideas underlying the show get unpacked, that’s our chance to dive in deeper.

Of course, that’s not to say that the show itself doesn’t also bring out the ideas, but we think that explicit conversation afterwards is really important.

What/who have been your influences?

We started off making interactive work in Canberra with no-one else around doing it - not in the way we were, anyway. We knew we weren’t the only ones making it, but we couldn’t easily find out who else was out there, and what their stuff looked like. So we made a lot of stuff up.

Our initial impetus was to do computer games live on stage. We adopted frameworks and conventions from old computer games, and adapted them to stage. Hacked gaming controllers (console controllers, joysticks) where the audience controlled the actors live onstage. Our first piece was a game called Playable Demo, where the audience piloted the actor through a short scene in the style of an old LucasArts adventure game, using a torchbeam as a mouse cursor on stage.

A little deeper into our practice, we’ve taken a lot from some of our closer collaborators. Applespiel, obviously, and Coney. Applespiel for their actual genuine expertise in participatory theatre (as opposed to our make-it-up-as-you-go style) and Coney for the superb philosophy and vocabulary around how a playing audience could and should be treated.

Finally, we’ve learned a lot from scientists, particularly those working in the field of participatory co-modelling. This is a form of practice whereby scientists collaboratively construct a working model of a social-ecological system - for example, a region of farmland, or a river system. Then they bring together stakeholders from that system to discuss and debate issues facing it, with the model as a platform to facilitate discussion and compromise. Their tools for audience engagement may be a little rudimentary, but the sophistication of the underlying models they’re using put most theatre-makers to shame.

Young Boho. Jack & David in A Prisoner's Dilemma, circa 2007.

Young Boho. Jack & David in A Prisoner's Dilemma, circa 2007.

What drew you to working in participatory/playful performance forms?

We started Boho in late 2006: Michael Bailey, Jack Lloyd, David Shaw and I. Jack and I had made an interactive scene called Playable Demo in 2005, based on old adventure games. (In the floppy disk era, you would often get a single scene from a larger game as a kind of interactive advert for the whole game.)

We took that format and combined it with the science of Game Theory to make our first show, A Prisoner’s Dilemma. Game Theory is a great tool for game-makers because it breaks real world scenarios into well-defined mathematical structures. We created a whole series of micro-games based on different Game Theory thought experiments (the Prisoner’s Dilemma, Chicken, Dictator, Ultimatum) and threaded a Harold Pinter-esque narrative through them.

That show really placed us in a very particular niche: ‘interactive science-theatre’. What even is that. But it was good to be able to label ourselves as something for a couple of years, even though now we’ve spilled out in a lot of different directions.

Food for the Great Hungers, 2009.

Food for the Great Hungers, 2009.

What's the benefit/advantage of playing with a participating audience?

Ahhh, well, the trick is what we all know now, you and me and all the artists making participatory theatre, which is: the audience is always participating - it’s just a question of how. Sitting passively in the dark watching and not talking is a form of participation - we’re just so trained by theatre conventions that we take it for granted and don’t realise it’s a choice, a compact we all (artists and audiences) agree on.

Same with making site-specific stuff - you realise that the theatre venue isn’t a necessity, it’s an option - you use it sometimes when the moment calls for it, at other times you let it go.

Whatever level of participation the audience engage in, that’s a trade-off. If the audience are moving around outdoors experiencing your work, they’re feeling much more exhileration, excitement, there’s opportunities for happy accidents and beautiful unique experiences, but you run the risk of losing their focus, of them being distracted, feeling lost or confused.

If the audience are seated quietly and watching a well-lit stage, that’s ideal for delivering complex information and making sure everyone sees the same thing, but you’re talking at them rather than having a conversation, and you run the risk of boring them / annoying them if they feel like they can’t leave.

We (Boho) choose the level of interaction based on what we want their experience to be, what we’re talking about, what we want to discuss. If we want to talk with them about how tipping points or regime shifts occur, maybe that’s best if we just explain it as clearly as we can, using whatever theatre imagery works best. But if we want to illustrate the challenges facing local government when they’re evacuating small communities from a potential volcano eruption, maybe we want to give them the experience of trying to make decisions and negotiate compromises with imperfect information.

True Logic of the Future, 2010. Pic by 'pling.

True Logic of the Future, 2010. Pic by 'pling.

What mechanics do you use to encourage and support player agency?

Typically our games are quite short, and there are lots of them throughout a show, interspersed with narrative / storytelling moments, or micro-lectures. That means we can guide the audience through the aesthetic experience quite closely, rather than setting it up at the beginning of the night and just letting them roam free.

That gives us a better chance of managing certain player dynamics - reining in hot players who are dominating the games, or drawing in quieter, more passive players.

But player agency? Not our highest priority, honestly. We’ve usually created quite a curated experience, and though each game is completely interactive, and the whole show has a lot of different states and outcomes (usually in the thousands, if you tally it all up), we’re not running a LARP - we have quite a detailed sense of where we want the audience to go, and we’re happy to take them there.

- David

For a high-speed example of all of these principles in action (more or less), you can check out Jack and Mick's 18-games-in-18-minutes performance at TEDx Canberra: